STORY BY GEOFF VIVIAN, PICTURES SUPPLIED

From The Koori Mail

It is a quarter to five in a Pilbara mining camp. Jerry Frewen drags himself out of bed and grabs a quick shower. It is an hour before dawn. He likes to be at his desk before the day shift arrives, so he doesn’t stay long in the small single-men’s quarters. He is grinning because it is the eighth day in his roster and he will knock off several hours before sunset and be back in Perth tonight. Just as he steps into his office, the first rays of the sun hit the red Pilbara dirt of an open cut iron ore mine.

It is a quarter to five in a Pilbara mining camp. Jerry Frewen drags himself out of bed and grabs a quick shower. It is an hour before dawn. He likes to be at his desk before the day shift arrives, so he doesn’t stay long in the small single-men’s quarters. He is grinning because it is the eighth day in his roster and he will knock off several hours before sunset and be back in Perth tonight. Just as he steps into his office, the first rays of the sun hit the red Pilbara dirt of an open cut iron ore mine.

Frewen is a drill and blast engineer at BHP’s Eastern Ridge mine, and unlike most of the professional staff, he is Aboriginal. He says most of the mine’s Aboriginal staff work as samplers, road crew, machinery operators and in the workshop, and there are plenty of job opportunities.

“A lot of mining companies are taking Aboriginal workers to increase their numbers,” he says. “Quite a few these days have commitments to maintaining a certain percentage of Indigenous workers. It’s theirs for the taking if they really want it.”

Silverlake Resources exploration manager Chris Banasik, who spends much of his time at a gold mining operation near Kalgoorlie, agrees there are opportunities for Aboriginal people who want to take them.

“The only thing we require of Aboriginal workers is the same as what we require of non-Aboriginal workers,” he says. “To be able to acquire the necessary training and be fit and healthy for work.”

So, what does the Fly-In, Fly-Out ( FIFO) lifestyle have to offer? At 27, Frewen says he likes the free time.

“Because of the eight days (on) and six-days-off roster, I can take eight days’ annual leave and get just over two weeks off,” he says. “It works out well for travelling and going on holidays. Generally once (a year) I go and visit friends in South East Asia. I don’t have any kids and I just really worry about myself.”

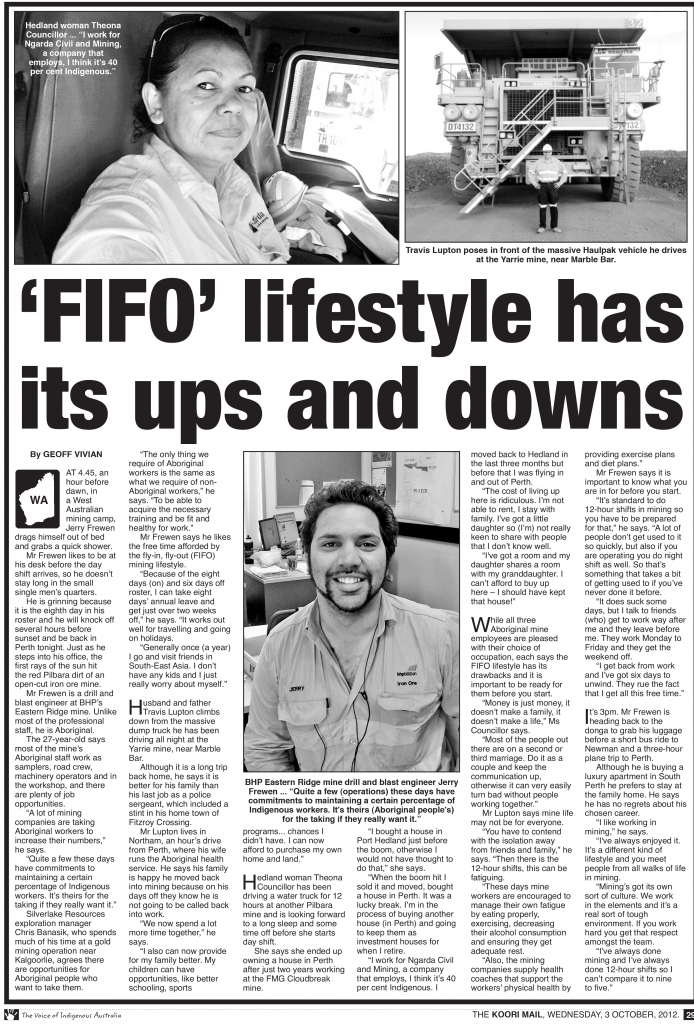

Husband and father Travis Lupton climbs down from the massive dump truck he has been driving all night at the Yarrie mine near Marble Bar. Although it is a long trip back home, he says it is better for his family than his last job as a police sergeant, which included a stint in his hometown of Fitzroy Crossing. He now lives in Northam, an hour’s drive north of Perth, where his wife runs the Aboriginal health service. He says his family is happy he moved back into mining because on his days off, they know he is not going to be called back into work.

“We now spend a lot more time together,” he says. “I also can now provide for my family better. My children can have opportunities, like better schooling, sports programs … chances I didn’t have. I can now afford to purchase my own home and land.”

Hedland woman Theona Councillor, who has been driving a water truck for twelve hours at another Pilbara mine, is looking forward to a long sleep and some time off before she starts day shift. She says she ended up owning a house in Perth after just two years working at the FMG Cloudbreak mine.

“I bought a house in Port Hedland just before the boom, otherwise I would not have thought to do that,” she says. “When the boom hit I sold it and moved, bought a house in Perth. It was a lucky break. I’m in the process of buying another house (in Perth) and going to keep them as investment houses for when I retire.”

“I (now) work for Ngarda Civil and Mining, a company that employs, I think it’s 40 per cent Indigenous. I moved back to Hedland in the last three months but before that I was flying in and out of Perth.

“The cost of living up here is ridiculous. I’m not able to rent, I stay with family. I’ve got a little daughter so (I’m) not really keen to share with people that I don’t know well. I’ve got a room and my daughter shares a room with my grand daughter. I can’t afford to buy up here – I should have kept that house!

“The first six months I was just so glad to be there but I didn’t actually plan financially. So maybe within the first three months of starting, go and see a financial planner and make use of that time because most people don’t want to stay there forever. While you are there just take advantage of what’s going.”

While all three Aboriginal mine employees are pleased with their choice of occupation, each of them says the FIFO lifestyle has its drawbacks and it is important to be ready for them before you start.

“Money is just money, it doesn’t make a family, it doesn’t make a life,” Theona says. “Most of the people out there are on a second or third marriage. Do it as a couple and keep the communication up, otherwise it can very easily turn bad without people working together.”

Travis says mine life may not be for everyone.

“You have to contend with the isolation away from friends and family,” he says. “Then there is the 12-hour shifts, this can be fatiguing. These days mine workers are encouraged to manage their own fatigue by eating properly, exercising, decreasing their alcohol consumption and ensuring they get adequate rest. Also the mining companies supply health coaches that support the workers’ physical health by providing exercise plans and diet plans.”

Jerry Frewen says it is important to know what you are in for before you start.

“It’s standard to do twelve-hour shifts in mining so you have to be prepared for that. A lot of people don’t get used to it so quickly, but also if you are operating you do night shift as well. So that’s something that takes a bit of getting used to if you’ve never done it before. It does suck some days but I talk to friends (who) get to work way after me and they leave before me. At the end of the day they work Monday to Friday and they get the weekend off. I get back from work and I’ve got six days to unwind. They rue the fact that I get all this free time.”

It is now 3.00 pm. Jerry is heading back to the donga to grab his luggage before a short bus ride to Newman and a three-hour plane trip to Perth. Although he is buying a luxury apartment in South Perth he prefers to stay at the family home. He says he has no regrets about his chosen career.

“I like working in mining,” he says. I’ve always enjoyed it, it’s a different kind of lifestyle and you meet people from all walks of life in mining. Mining’s got its own sort of culture. We work in the elements and it’s a real sort of tough environment. If you work hard you get that respect amongst the team. I’ve always done mining and I’ve always done twelve-hour shifts so I can’t compare it to nine to five.”